[Back Post] Japan with Peko-chan 2017 #6.1/9 - Nagasaki, Part I

So, now to continue with back-posting the late 2017 travel series, from where we left off in the Tokyo (Part 5).... We deviated from our original plan to stick to only the Chuubu region in favour of making a run to Nagasaki, and went to Tokyo for a few days before catching a domestic flight to Nagasaki. (In hindsight this was super silly. Especially right now, because Hubs is planning a trip to Kyushu. *facepalm*) While at Nagasaki, we visited various spots that speak of Nagasaki's rich history. We first started with its former foreign settlements, before exploring its history with Christianity and its more modern face as the city that faced the 2nd atomic bomb in WWII (see Nagasaki Part II).

|

| Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Nagasaki has a rich history that is deeply connected to the world outside Japan, and various global events, making it quite different from the historical narratives of cities like Tokyo and Kyoto. Nagasaki is mostly remembered for the 2nd atomic bombing during WWII. But long before WWII, Nagasaki was Japan's 2nd major international port and Japan's window to the world. Since ancient times, there had been exchanges between Japan and China. From at least 607 AD, Japanese diplomatic envoys travelled to Tang dynasty China by the sea route off Nagasaki's coast, through the Iki, Tsushima and Goto Islands. Japan was trading with China and Korea through its ports in Kyushu long before the arrival of the Portuguese and the start of Nanban trade in Japan.

|

| Model of a 16th century Portuguese carrack "Caracca Atlantica", Dejima, Nagasaki. |

Nanban trade began some time in 1543 (Sengoku era), when the Portuguese first arrived in Japan, in Tanegashima, an island south of Kagoshima. During the course of the Nanban trade, the Portuguese introduced the predecessors of the castella cake and tempura (mentioned in our Enoshima 2017 visit), as well as Christianity. While castella and tempura had innocuous histories in Japan, the history of Christianity in Japan was bloody and oppressive. As Nagasaki was the centre of Catholicism in Japan, it also became the centre in which the Tokugawa shogunate persecuted those who practised and proselytized Christianity (see Nagasaki Part II).

|

| Model of a Dutch Freisland naval ship, Dejima, Nagasaki. |

The Dutch arrived in 1600 as survivors of a Dutch expedition against Portuguese and Spanish settlements in Africa and Asia. That was the beginning of Dutch presence in Japan. The Dutch began trade with Japan, through the Dutch East India Co, from their trading post in Hirado. During the sakoku period (1633-1853), Nagasaki was one of the 4 places in Japan where foreign trade and foreign settlements were allowed, and only the Dutch and Chinese were permitted to trade at Nagasaki. At the beginning, the Portuguese were confined to Dejima (more below), the Dutch in Hirado, and the Chinese in the Chinese quarter (more below). Following the expulsion of the Portuguese in 1639 as a response to the Shimabara Rebellion, the Dutch were forced to move to Dejima around 1641. Along with trade, the Dutch introduced beer, coffee, chocolate, cabbage, tomatoes, clay smoking pipes, among other things. The Dutch also greatly contributed to the body of Western scientific and technological knowledge in Japan, called Rangaku at the time (more below).

|

| Nakashimagawa, Dejima on the left, modern-day Nagasaki city on the right, view from Dejima Omotemon-bashi. |

Dutch trade gradually declined due to restrictions by the Tokugawa Bafuku on precious metals; copper and silver were lucrative commodities to the Dutch trade. Another factor for its decline was the financial difficulties faced by the Dutch East India Co. arising from wars and political unrest in the Netherlands. The Dutch eventually also lost their monopoly on the global spice trade to the British. These events also have a place in the histories of my country and region. Subsequently, Nagasaki was forcibly opened to trade with America, England, France and Russia through the 1854 Kanagawa Treaty the 1858 Harris Treaty, the Ansei Treaties, etc., thus ending Dutch trade monopoly with Japan. The opening of Nagasaki through these unequal treaties led to the establishment of the Nagasaki foreign settlement (more below). Around this time, the Chinese trade also declined considerably, partly due to the competition as a result of these unequal treaties, as well as growing internal civil unrest in China starting with the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864).

Nagasaki Foreign Settlement

We first made our way to the Nagasaki foreign settlement in the Oura district. In terms of chronology, the area was designated as the new foreign settlement following the 1858 Harris Treaty and Ansei Treaties, at around 1860. Up until WWII, Oura functioned as an important centre and settlement area for Westerners in Japan. Most of the Western residences that remain are located (some were re-located) in the Glover Garden (below). However, the Oura district still very much retains some of its old atmosphere, with a few original landmarks left.

Former Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank Nagasaki Branch

|

| Former Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank, Nagasaki Branch |

In the Nagasaki foreign settlement stands the Former Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank Nagasaki Branch (Kyu Honkon Shanhai Ginko Nagasaki-ten). In 1896, the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank (now HSBC) opened a branch in Nagasaki and was the city's first foreign bank. The Neoclassical building was built in 1904 and was designed by Japanese architect Shimoda Kikutarou and is the only building designed by Shimoda that remains.

The building stands in the area that was once known as the Oura Bund or the Nagasaki Bund, and was the main street of Nagasaki's foreign settlement, as well as the face it presented to people who arrived at the port. This area is also where the Nagasaki Hotel (see below) once stood. Back in the day, the Bund was lined with grand brick and stone Western-style buildings that housed the foreign consulates, companies and banks. The foreign hotels, restaurants, bars and shops occupied the side streets and back quarters, and the Western-styled residential buildings occupied the back, extending up the hillside areas of Higashiyamate and Minamiyamate. The overall atmosphere was very European, with the Western-styled buildings, brick walls, and tree-lined cobble-stoned streets. I'm reminded of the other foreign settlements in Japan, like in Kobe (Part 9) and Yokohama, and these characteristics seem to be typical of Western foreign settlements.

Along the way, we came to the Dutch Slope (Oranda-zaka). It's a sloping stone street through the residences of foreigners who settled in Nagasaki in the late 1850s following the signing of the unequal treaties (as mentioned above). At the time, the Japanese simply referred to all Westerners as Oranda, meaning Hollander, since the Dutch had been trading with Japan since the 17th century.

|

| The Dutch Slope (Oranda-zaka), Nagasaki |

Construction of buildings in the Nagasaki foreign settlement began in 1860, immediately after the area was designated. Foreign settlers renting land had specifications regarding the sizes and shapes of doors, windows, floors, chimneys and other Western styled fixtures. The Japanese builders, however, used traditional Japanese techniques and materials such as cedar, kawara roof tiles, Amakusa sandstone and such. They also incorporated modern materials, red bricks produced by Nagasaki Iron Works, as well as glass, brass door knobs, iron fireplace grates and others which they imported from Shanghai. The result was an amalgamation of Japanese and European architectural style. These foreign buildings and residences became referred to as oranda-yashiki ("Hollander residence") in Nagasaki, and variously as yofukenchiku ("Western style architecture"), ijinkan ("foreigner's building", like in Kobe, Part 9), and yōkan ("Western building") elsewhere. As mentioned, many of the foreign residences were relocated to the Glover Garden (below).

Also in the Nagasaki foreign settlement were the foreign consulates, various foreign clubs and organisations. The consulates served the needs of the citizens of their respective countries, as well as maintained relations with the Japanese shogunate, business representatives and citizens. More importantly, under the system of extraterritoriality guaranteed by the unequal treaties, the foreign residents enjoyed immunity to Japanese law and were instead subject to the jurisdiction of their respective consulates. Thus the consulates also served as consular courts that tried the foreign residents, and also employed constables to maintain law and order among the foreign residents.

On our way to the Glover Garden, we visited the Oura Catholic Church (Oura Tenshudo) (Part II), a church dedicated to the 26 Catholics who were crucified by Japan's 2nd unifier Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1597, and is a reminder of the history of Hidden Christians in Nagasaki (more in Part II).

Glover Garden

We next went to the Glover Garden, a park in the hillside Minami-yamate area, where most of the foreign residences are located and preserved. Glover Garden's namesake is Scottish merchant Thomas Blake Glover who was based in Nagasaki during the Bakumatsu and Meiji periods. Glover was a key figure who made many contributions to Japan, including helping the anti-Bafuku forces in toppling the Tokugawa Shogunate, and the industrialisation of Japan. Glover's former residence, Glover House (below), is situated within the Glover Garden, and his grave is located at the Sakamoto International Cemetery (below).

Former Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2

|

| Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Former Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2 (Kyu Mitsubishi Dokku Hausu) was built in 1896, during the Meiji era. The 2-storey wooden building served as lodgings for crew whenever ships docked at the Mitsubishi shipyard. It was relocated to the Glover Garden. So, one might ask how are Glover and the Mitsubishi Group related such that a Mitsubishi dock house should be relocated here? Well, Thomas Glover was a key figure to Mitsubishi who helped develop areas that became the pillars of Mitsubishi's early growth and diversification. Glover was not only an adviser to Mitsubishi but also a friend of its founder Iwasaki Yatarou, who had business dealings with Glover before the Meiji Restoration. Glover had helped develop Japan's first Western mechanised coal mine in Takashima (in 1869), which was acquired by Mitsubishi in 1881. Following Mitsubishi's acquisition, Glover was retained to handle the company's trading operations, and became an advisor to Mitsubishi on the adoption and development of new technology, as well as the company's foreign affairs. Glover also built Japan's first Western-style dry dock in Nagasaki Harbour, a technology which Mitsubishi adopted. Together with Iwasaki Yanosuke (Iwasaki Yataro's brother, Mitsubishi's 2nd president), Glover also helped establish the Japan Brewery (now Kirin Brewery).

|

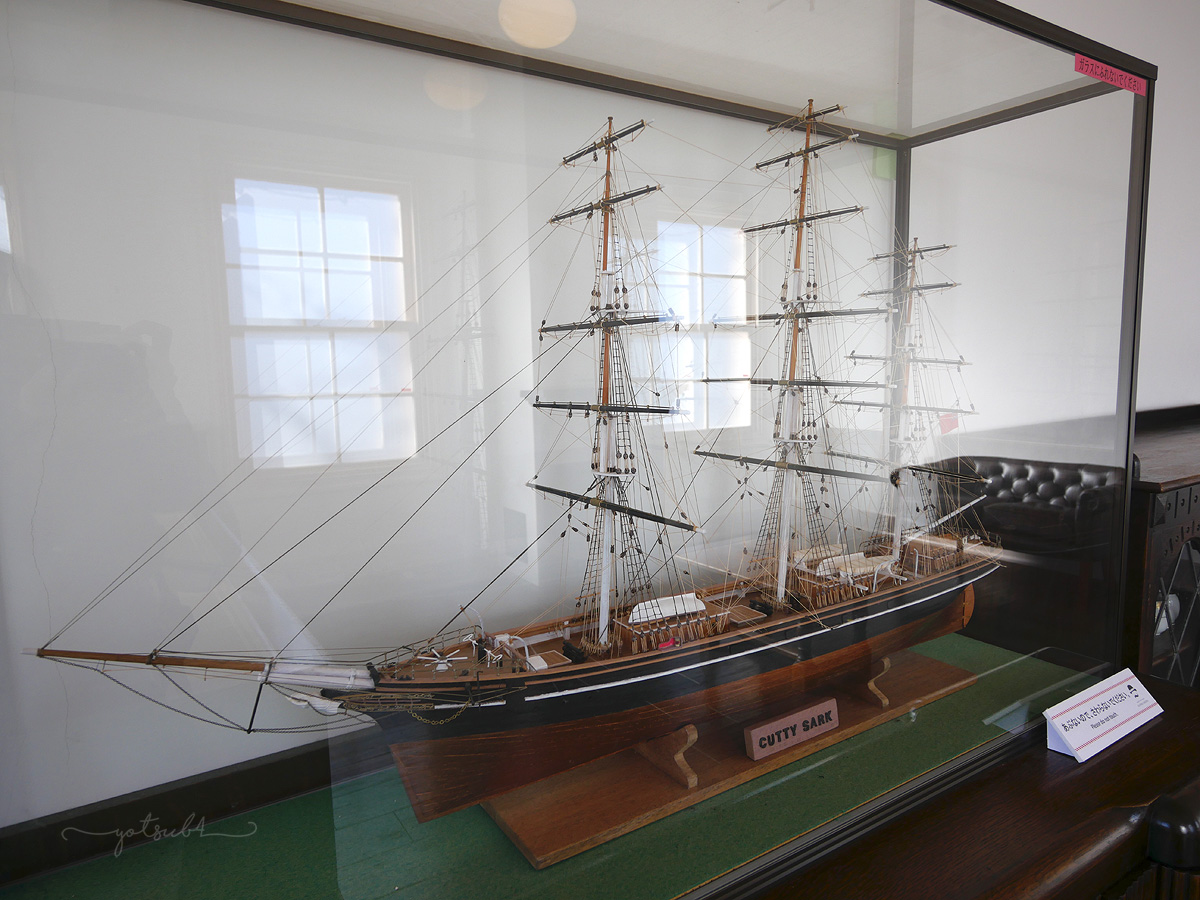

| Replica of the Cutty Sark, Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2 contains a number of replica models of ships from the various countries that Japan traded with at the time, i.e. Portugal, China, the Netherlands, the UK, France, etc. Hubby used to sail competitively (during his school days) and is a fan of maritime replicas, so he had a great time looking at the models, absolutely fascinated with the details. From across the room, he recognised the replica of the Cutty Sark, yes, without even seeing the name plate. When I asked him how he knew, he started talking about its features and details, as well as its place in maritime history. So, the Cutty Sark was a historic record-breaking British clipper that was built in 1869 in Scotland, originally designed to carry tea from China to Britain. Although she wasn't the fastest ship in the tea trade, she was one of the fastest sailing ships of her time, and travelled the world and visited every major port in the world at the time. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, she was subsequently employed in the Australian wool trade (1883-95) where she held the record as the fastest sailing ship for 10 years. I was surprised to learn that the actual ship still exists intact, and is exhibited at the UK Royal Museums Greenwich. Coincidentally, I was re-watching the anime Kuroshitsuji over the weekend and the Cutty Sark was mentioned in Season 1 episode 19, along with a short scene of her looming over a rowboat, with her figurehead in view. The scene centred on her speed, her original purpose as a tea clipper, and her namesake Nannie Dee, a fictional witch created by renowned Scottish poet Robert Burns in his 1790 poem Tam o'Shanter (also the model for her figurehead).

|

| View from the Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Dock House overlooks Nagasaki Harbour and the Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard. The shipyard was first established in 1856 by the Shogunate with the assistance of Dutch engineers but transferred to Mitsubishi in 1887. From the 2nd floor, the Mitsubishi No. 3 dry dock, the Mitsubishi guest house, the Mitsubishi former pattern shop, and the giant cantilever crane can be seen in the shipyard. These four components relate to the shipyard's expansion to cope with increased shipbuilding capacity in the late Meiji period, and are UNESCO World Heritage listed.

What amazes me is these components continue to be in use today, some 100-plus years on. The No. 3 dry dock (1905) is the only dry dock from the Meiji period that is still in operation today, and the original pumps and motors still continue to perform their functions. The giant cantilever crane (1909) is Japan's first electric-powered crane of its type, can lift 150 tones and is also still in operation. The Guest House (1904) was originally designed by Japanese architect Sone Tatsuzou as the residence for the shipyard's director. Today, it is used as a guest house for the shipyard's important clients. The former pattern shop (1898) is now the shipyard's museum, and was formerly built to produce wooden patterns for castings.

|

| Mitsubishi Dock House No. 2, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

In another room was a large poster of Sakamoto Ryouma, the Tosa samurai who was a key figure of the Meiji Restoration. Sakamoto was regarded as one of the fathers of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Sakamoto worked under the patronage of Japanese naval engineer Katsu Yasuyoshi. Their relationship is an interesting story. Sakamoto and Katsu were initially opposed in ideology. Sakamoto was an adherent of the sonnou joui movement, which opposed Western influence, sought to overthrow the Shogunate and restore Imperial power. On the other hand, Katsu was educated in Western military science, worked for the Shogunate in posts where he regularly liaised with Westerners, and actively advocated for the modernisation and Westernisation of Japan. In fact, Sakamoto once tried to assassinate Katsu. After Sakamoto was convinced otherwise, the two worked on the development of a modern naval force, and Sakamoto was a student at the naval training college in Kobe headed by Katsu. Later in 1865, Sakamoto founded Kameyama Shachuu, a small merchant shipping company in Nagasaki, and purchased a steamship from Thomas Glover. The company was later renamed Kaientai, and acted as a private auxiliary navy for the anti-Bakufu forces. Ironically, in time, Sakamoto came to admire democratic principles of equality and governance espoused by various Western philosophies. In 1867, while onboard a ship off Nagasaki, Sakamoto discussed with fellow Tosa samurai Gotou Shoujirou the future government model for Japan, and penned the Senchu Hassaku, a proposal outlining Japan's need for a written Constitution, a democratically elected legislature, formation of a national army and navy, regulation of exchange rates, etc.

|

| One of Japan's earliest asphalt roads, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

One of earliest asphalt roads in Japan, supposedly this path was paved so that British merchant Frederick Ringer (1838-1907) could reach his house, the former Ringer House (see below) by rickshaw.

|

| Japan's first tennis court, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

This is a stone roller that was used on the tennis lawns built by Frederick Ringer. Apparently Ringer also built Japan's first tennis courts in the early Meiji era.

Former Gatekeeper's Station

|

| Former Gatekeeper's Station, Nagasaki Commercial College, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Former Gatekeeper's Station (Kyū Nagasaki Kōshōhyōmon'eisho) was erected near the entrance of the Nagasaki Commercial College (Nagasaki Kōtō Shōgyō Gakkō), but was relocated to the Glover Garden in 1976. Established in 1905, the school was later renamed the Nagasaki College of Economics (Nagasaki Keizai Senmon Gakkō) in 1945, and is one of Nagasaki University's predecessors.

Former Residence of the President of the Nagasaki District Court

|

| Former Residence of President of the Nagasaki District Court, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Former Residence of the President of the Nagasaki District Court (Kyū Nagasaki Chihōsai Bansho Chōsa) building was built in 1883 (Meiji era) at Uemachi, and was originally a residence for officials of the Nagasaki Court of Appeals. It later became the official residence of the president of the Nagasaki District Court. Relocated to the Glover Garden in 1979, the building is the only surviving Western styled government structure that stood outside the foreign settlement at the time.

Former Walker House

|

| Former Walker House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Next was the Former Walker House (Kyū Uōka Jūtaku), the residence of English master mariner and businessman Robert Walker Jr (1882-1958). The house was built around the 1890s. Walker Jr acquired it in 1915 and lived here with his family until his death in 1958, following which his wife Mabel Shigeko Walker donated the building to Nagasaki. The building was relocated to the Glover Garden in 1974. Robert Walker Jr's father and uncle were both master mariners who had deep ties to Mitsubishi. His uncle Wilson Walker (1845-1914) came to Japan in 1868, while his father, Robert N. Walker (1851-1941) came to Japan in 1874. Both of his father and uncle commanded steamships for Mitsubishi and later Nippon Yusen Kaisha (present-day Nippon Yūsen, aka NYK Line), when Mitsubishi merged with the Kyodo Unyu Kaisha in 1885. Before working for Mitsubishi, Wilson Walker also commanded steamships for Thomas Glover's company Glover & Co., and later Frederick Ringer's company Holme, Ringer & Co. He was appointed superintending captain of the Mitsubishi Mail Steamship Co. and was instrumental in establishing the Yokohama-Shanghai line, Japan's first passenger liner service. He later assisted Thomas Glover in the establishment of the Japan Brewery (the predecessor of Kirin). Walker Snr established the ship chandelling business R.N. Walker & Co. in Nagasaki in 1898, and later in 1895 1904 he started the Banzai Aerated Water Factory which began mass production of ginger ale and other carbonated drinks in Japan. Walker Jr took over these businesses in 1908 when Walker Snr emigrated to Canada.

|

| Inside the Former Walker House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The house is filled with items from the Glover and Walker families. It's one of my favourites in the Glover Garden, in terms of the interiors, because it's bright and filled with light.

Nagasaki Masonic Lodge Gate

|

| The Nagasaki Masonic Lodge Gate, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Next to the Former Walker House is the Freemason Lodge Gate, the front gate of the former Nagasaki Masonic Lodge, a Scottish Masonic lodge. The Lodge was founded in 1885 but surrendered its charter around 1911. The gate was originally located in front of the Lodge at No. 47 Sagarimatsu, but was relocated to the Glover Garden.

Former Ringer House

|

| Former Ringer House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Further down the path was the Former Ringer House (Kyū Ringa Jūtaku), the former residence of British merchant Frederick Ringer (1838-1907) and his son Sydney A. Ringer. In 1965, it was sold to Nagasaki when Sydney returned to England. Built in 1868-1869, the house is an early Meiji era bungalow that fuses Western and Japanese styles and elements. The building has verandas on 3 sides, sandstone walls, a hipped roof with ceramic tiles and coal-burning fireplaces. The granite stone of the veranda floor was imported from Vladivostok, while the square pillars supporting the veranda roof was made of Amakusa sandstone. It was designated a National Important Cultural Asset in 1966.

Before Ringer arrived in Nagasaki, he was a tea inspector in China with a prominent English company. He then came to Nagasaki in 1865 to join Glover & Co. as a supervisor of tea production and export. In 1868 he joined with Edward Z. Holme to form Holme, Ringer & Co. The company originally began as a tea firing and export business, but later expanded into other businesses such as flour milling, whaling, kerosene storage and electricity production, and then further expanded to include export of other lucrative trade products, shipping, coal and munitions. In 1888, the company became Lloyd's representative in Nagasaki, as well as the local agent for many other foreign insurance, banking and shipping companies. The company further expanded into East Asia and Russia. The company also conducted business with Mitsubishi and Mitsui (present-day Mitsui Group.

|

| Sitting room of the Former Ringer House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Like Thomas Glover (see above), Ringer was also an active participant and leader in the Nagasaki foreign settlement. He served on the Municipal Council, and was Consul and Acting Consul for various consulates. Similarly, he made several contributions to the industralisation of Japan, such as the mechanisation of flour milling, steam laundry, petroleum storage facilities, stevedoring, etc. He also played a key role in the construction of the Nagasaki Waterworks.

Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) enabled Japan to expand its fishing grounds, which greatly benefitted Nagasaki. In this area, Ringer established the Nagasaki Steamboat Fishery and appointed Glover's son Kuraba Tomisaburou (more below) as the director. Tomisaburou imported Japan's first steam trawler and conducted, together with experts, the first trawling experiments, making further contributions to the Nagasaki economy trawl fishing as a result. Naturally this was protested against by the local Japanese fishermen who used traditional methods. Due to this technology, Tomisaburou was also able to put together the Glover Fish Atlas (see below). Ironically, today we are experiencing a reversal, as we now discourage methods like trawling due to the damage these have on the ocean ecology, and push for sustainable fishing methods, which include some of these traditional methods used by Japanese fisherfolk in the past.

|

| Former Ringer House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

In the late 1890s, with Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), Nagasaki experienced an economic windfall as a coal depot, supply harbour and rest place for foreign warships and merchant ships. As a result, Ringer became the dominant foreign merchant in Nagasaki, and grew extremely prosperous. With his wealth and connections, he established the English daily newspaper Nagasaki Press in 1897 (closed in 1928), and constructed the Nagasaki Hotel in 1898 (closed in 1908). At the time, the Nagasaki Hotel stood along the Oura Bund, next to the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank building (above). It was considered one of the finest Western styled hotels in the East. Its architecture was designed by British architect Josiah Conder. It had fine views of Nagasaki Harbour, state-of-the-art technology (electricity, private telephones, running potable water), luxurious facilities (wine cellar, beauty salon), opulent furnishing and silver cutlery, as well as a French chef. The waterworks system in the Nagasaki Hotel was designed by a British engineer and was, at the time, Japan's third modern waterworks.

|

| Miniature of the former Nagasaki Hotel, displayed in the Former Ringer House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The silver cutlery set from the Nagasaki Hotel had been produced by British silverware maker Mappin & Webb (now an international jewellery company, purveyors to the British royal family since 1897). Each utensil was galvanised with gold and silver, and some were carved with the letters "NHL", the hotel's initials. The cutlery set and ceramic dishes on display were donated to Nagasaki City in June 2013 by the Nara Hotel, which found a large quantity of the tableware during renovations. The Nara Hotel made replicas of ceramic dishes and other tableware that had been originally used at the Nagasaki Hotel. The dishes also bore the letters "NHL".

|

| The cutlery from the former Nagasaki Hotel |

Business at the Nagasaki Hotel was good until the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Although it ended with Japan's victory, Nagasaki's international port trade declined, affecting many of the hotels in Nagasaki. Business at the Nagasaki declined considerably and the hotel went bankrupt in 1904. Ringer's company took over but had to close it in 1908, a few weeks after Ringer's death in England. Shortly afterwards, the hotel's furnishings and property were sold. Ten years later, Japanese merchant Mori Arayoshi attempted to revive the hotel but business again failed and it was permanently closed in 1924, and the building was demolished soon afterwards.

Displayed alongside the Nagasaki Hotel exhibits were also costumes from Puccini's Madame Butterfly. They were beautiful, but I found this display rather odd, as the opera is more closely associated with the Glover House. Well, more on that later.

|

| Costumes from Puccini's Madame Butterfly in the Former Ringer House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The costumes and accessories on display were from operas performed by Japanese opera singer Miura Tamaki (1884-1946). Miura performed the role of Cho-cho in Madame Butterfly. The headdresses from Puccini's Turandot and Mascagni's Iris in particular were especially elaborate.

| |

|

So, a bit of operatic trivia here. In Iris, Miura performed with Japanese tenor Fujiwara Yoshie (1898-1976). Fujiwara founded the Fujiwara Opera Company in 1934 and later became a big name in opera in 20th century Japan.

| |

|

So, I was puzzled about the opera exhibits in the Ringer House, considering any reference to Madame Butterfly is associated with the Glover House. In fact, it's downright ironic, as Ringer was reportedly against interracial marriage and one of his firm partners fathered a son with a geisha. What makes it even more ironic is that this son was Fujiwara Yoshie.

It's not just the opera costumes. Not far from the Former Walker House is a statue of Puccini and a statue of Tamaki Miura as Cho-cho in Madam Butterfly. I photograph the latter, unfortunately. The Madame Butterfly displays may be a result of authorities trying to promote the Glover Garden and capitalise on anything that could boost tourism.

|

| Statue of Puccini, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The Glover House (more below) is sometimes referred to as the Madame Butterfly House. This was a nickname coined by American occupation forces in post-WWII, possibly because the house and the location fit with the setting of Madame Butterfly, and also Glover's marriage to a Japanese woman. Considering its story and its source material (Pierre Loti's novel Madame Chrysanthème), one can't help drawing some parallels, e.g. Glover's naval connections and his relations with Japanese women (his wife Tsuru and the biological mother of his son Tomisaburo), tenuous as these parallels may be. Glover was no Pinkerton and Tsuru was no Cho-Cho! The opera and the novel clearly reference the social relations and conditions between foreigners and Japanese at the time. But otherwise there is really no evidence of any real connection or related history.

Actually, considering Frederick Ringer's contributions to Japan, it is very tragic what happened to his family after his death. Ringer had 3 children, Fred, Sydney and Lina, all born in Nagasaki. In the 1930s, as the Japanese government became increasingly militant, the environment for foreigners deteriorated. With the onset of WWII, the Ringers had to shut down Holme & Ringer Co., which took place some time in 1940. The family was accused of spying by the Japanese government. Sydney and his wife fled to Shanghai, but were later arrested and became Japanese prisoners of war at a camp. Ringer's grandsons by Sydney (Michael and Vanya) were arrested and expelled from Japan in August 1940. Both of them joined the British Indian Army and fought against the Japanese Imperial Army in Malaya. Vanya was killed in 1942. Michael was evacuated to Singapore before being captured in Sumatra, and became a Japanese prisoner of war. Following the end of WWII, Michael apparently returned to Japan where he dealt with the family's properties, which had been confiscated or vandalised, and later returned to England. The family's only remaining legacy in Japan is the former Ringer House and the company Holme Ringer & Co., which was restarted by its former Japanese employees, now based in Kitakyushu.

Former Alt House

|

| Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

We next came to the Former Alt House (Kyū Oruto Jūtaku), the former residence of British merchant William J. Alt (1840-1905). William Alt arrived in Nagasaki in 1859 and established Alt & Co, which engaged in the tea trade and other businesses. Alt collaborated with Ōura Kei (1828-1884) in gathering tea from all over Kyushu and exporting it worldwide. Kei was a female merchant and was one of the most influential women of Nagasaki, she is today credited as a pioneer of exporting Japanese green tea. Alt also had a close friendship and business ties with Iwasaki Yatarou, Mitsubishi's founder (see above). It has been said that while out with Iwasaki at the foreign settlement one day, Alt was able to briefly leave the foreign settlement to have a glimpse outside because Iwasaki had asked a sentry to turn a blind eye. In the 1867 Icarus affair, in which 2 British Royal Navy sailors were murdered by an unknown swordsman, Kaientai, Sakamoto's company (as mentioned above), was suspected of the murders. Alt appeared with Iwasaki before the British Consulate to appeal the innocence of Kaientai.

The Alt House is also one of my favourites in the Glover Garden, both for its exterior facade and interiors. The house was designed by a British architect and constructed in 1865 by Japanese master carpenter Koyama Hidenoshin, who also constructed the Oura Catholic Church (see Nagasaki Part II) and the Glover House (below).

|

| Peko-chan at the Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki. |

The house has a wide veranda with a row of Tuscan columns, a portico with a gabled roof, and a fountain at the front. The stone walls and columns use Amakusa sandstone (like the former Ringer House, above) while the Japanese-styled roof used traditional ceramic tiles, known as kawara-yane. It is the largest house among the stone Western styled houses that remain in Nagasaki, and was designated a National Important Cultural Asset in 1972.

|

| Dining room of the Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Compared to the rooms of the other foreign residences, the rooms of the Alt House are relatively small, but have high ceilings and tall windows, giving the rooms a bright, light and airy appearance. The furnishings also seemed lighter and more graceful than the other houses, giving the place a rather feminine and elegant feel. Somehow I just like that a lot, that bright, airy and graceful atmosphere of the house.

|

| Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

William Alt was also a prosperous merchant and an active member in the affairs of the Nagasaki foreign settlement. In 1861, he served as a leader of the settlement's Municipal Counsel and was a member of the committee that led the newly created Chamber of Commerce.

|

| Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Alt lived with his family in this house, but later moved briefly to Osaka and Yokohama. Business for Alt & Co. was very good, but Alt returned to England for good in 1871, due to his poor health. After the Alts returned to England, the house was briefly used as a school building by the Kwassui Academy (present-day, Kwassui Women's University) in 1880. It then became home to various foreign residents in Nagasaki, including American Consul W.H. Abercombie who also used the building as the American consulate.

In 1903, it became a property of Fred Ringer, the elder son of Frederick Ringer, until Fred's death in 1940. As mentioned above, things went really downhill for the Ringer family at the onset of WWII, particularly as the family was accused of spying. After Fred's death, his widow continued to live in the house, but in 1941, she was interrogated by the Kempeitai on suspicion of being a spy, and imprisoned until 1942. She soon left Japan to return to England. In 1943, the house was sold to the Kawanami Toyosaku, the owner of Kawanami Shipyard. After WWII, it served as a tenement house and was later acquired by Nagasaki City in 1970, then refurbished and relocated to the Glover Garden.

|

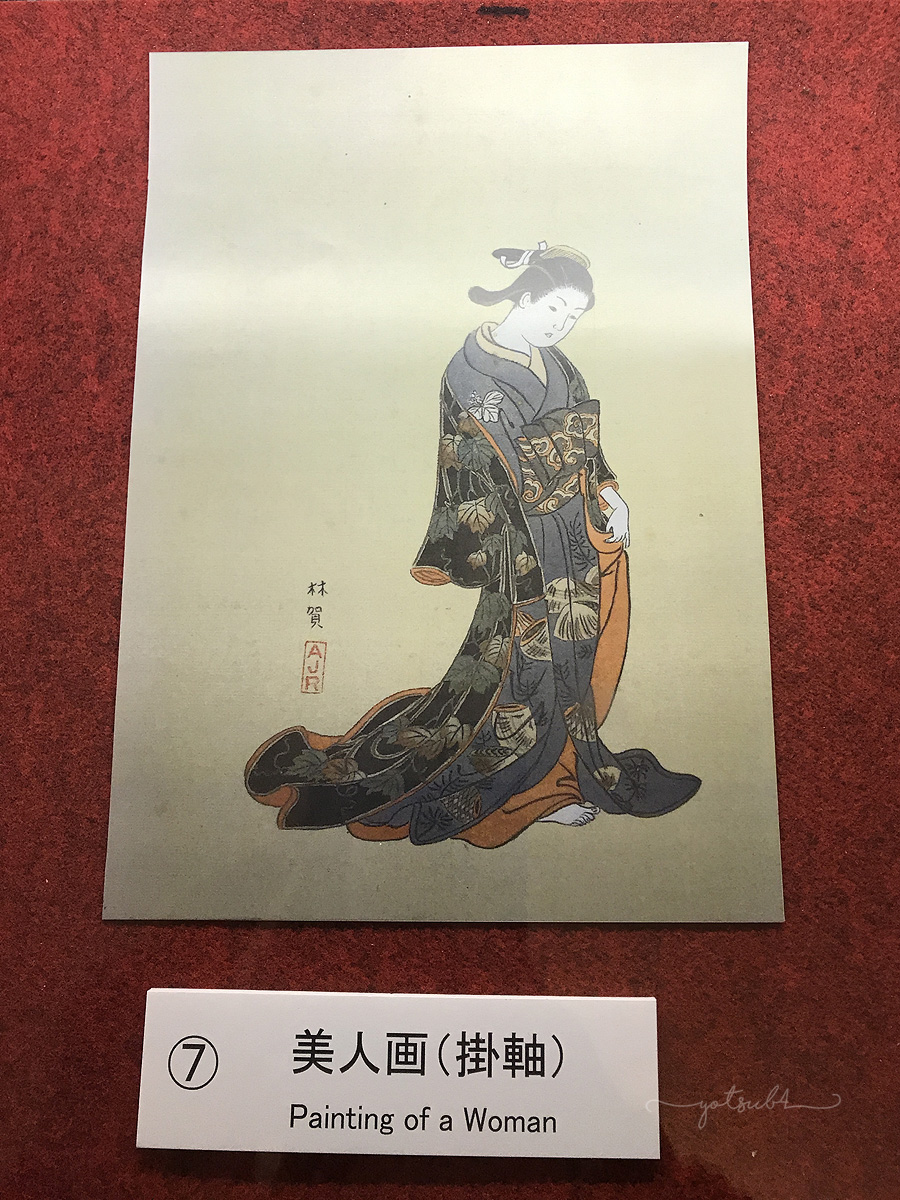

| Painting of a Woman by Alcidie J. Ringer, former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Among the various exhibits in the former Alt House are items once belonging to the Ringer family, mostly Frederick Ringer's grandchildren by Fred Ringer. One of the items was a painting by granddaughter Alcidie J. Ringer who used traditional Japanese painting techniques. In her signature, "Ringer" is phonetically rendered as Rin-ga.

|

| Dollhouse miniatures on display at the Former Alt House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Yeah, obviously I'd be drawn to the dolly miniatures! So this Japanese doll house belonged to Alcidie Ringer, and includes a set of miniature furnishings made from pottery clay, glaze, cloth, straw and other authentic materials. These miniatures are apparently invaluable artifacts as this type of doll house was produced only during a short period in the 1920s.

Former Steele Memorial Academy

|

| Former Steele Memorial Academy, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The next building we passed was the Former Steele Memorial Academy (Kyū Suchiiru Kinen Gakkō), a Reform Church missionary school in the 1880s. Relocated to the Glover Garden in 1973, the building was originally located on the former site of the Nagasaki British Consulate at No. 9 Higashiyamate. At the time, the Higashiyamate district was the location of several missionary schools. In 1897, as many as 13 of the 17 plots in the district were missionary schools and residences for the foreign teachers and missionaries, thus giving the district the nickname "Missionary Hill".

The creation of the academy was headed by American missionary Henry Stout (1838-1912), after the ban on Christianity was officially lifted. The building was built in 1887 under the supervision of Dutch-born American missionary Albert Oltmans (1854-1939) who became the school's first principal. It was named after William H. Steele (1818-1905), a minister and president of the Reformed Church in America's Board of Foreign Missions. Steele had donated funds in memory of his deceased son. The academy was a boys' school and many of the students were Japanese. Until 1932, the school provided a unique style of education in the English language. At some point in time (1891?) it was renamed the Tozan Gakuin. Subsequently, in 1932, it became part of the Meiji Gakuin group of schools (present-day Meiji Gakuin University) but closed a year later. The building was later used by other Catholic schools until finally in 1972, the Catholic school Kaisei Gakuen donated the building to Nagasaki City.

|

| Former Steele Memorial Academy, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

The first floor of the building displays illustrations of the various marine species found around Nagasaki. When Kuroba Tomisaburou introduced fish trawling to Japan (mentioned above), he would often visit the waterfront to watch the fish being landed.

|

| Kuroba Tomisaburou, son of Thomas Glover |

When Tomisaburou studied biology at the University of Pennsylvania, he had been interested in the biological illustrations of various fish and animal species in the textbooks, and knew that no such equivalent had been produced in Japan. Seeing the variety of fish that came up in the trawler nets, he began to systematically research fish species in the area around Nagasaki and to compile a comprehensive fish atlas. This research task that Tomisaburou undertook eventually resulted in the "Glover Fish Atlas", known formally as Atlas of Fish Species in the Waters off West and South Japan.

|

| Illustration on display at the Former Steele Memorial Academy, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

To create the Atlas, Tomisaburou had to show examples of the illustration style to the local artist he hired. The Atlas took 21 years to complete, through a long process of trial and error, and the illustrations were made by 4 successive artists. It contained 823 detailed watercolour paintings, including 700 illustrations of 558 fish species and 123 illustrations of shell and whale species, all with names in both Latin and local Japanese dialects written by Tomisaburou. At the time, the Atlas was a significant contribution to the scientific documentation and study of fish species in Japan. Tomisaburou's life work and prized possession, the Atlas is considered as one of the 4 greatest hand-painted fish atlases in Japan.

Jiyūtei

|

| Jiyutei, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Along the way, we passed Jiyūtei, the first Western restaurant. It opened in 1863 under the name "Irabayashi-tei" by its founder Kusano Jokichi, a Japanese chef who learnt the foundation of European cuisine from the Dutch consul general in Dejima. The building was first built in 1878 and was originally located in the centre of Nagasaki, near the Suwa Shrine. It provided a venue for social gatherings and parties for both Japanese and foreign guests. Among Jiyūtei's customers was former US President Ulysses Grant, who visited Nagasaki in 1879. Following Kusano's death, the Jiyūtei closed in 1887. The building was acquired by the Japanese government and used as a public prosecutor's office until 1974, when it was donated to the Glover Garden. It was relocated to the Glover Garden where it continues to operate as a coffee shop, which serves castella cake, among other things.

Former Glover House

|

| Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

We came now to the main highlight of the Glover Garden, the Former Glover House (Kyū Kuraba Jūtaku). The house is a designated Important Cultural Property of Japan and a UNESCO World Heritage site. The house is an example of the fusion of British colonial and traditional Japanese styles. For instance, the interior are European in style, but the kawara roof tiles and walls are done in Japanese style. It is said to be the oldest surviving wooden Western style house in Japan. The house was built by Koyama Hidenoshin, who also built the Oura Catholic Church (see Nagasaki Part II) and Former Alt House (above).

As mentioned, Glover was a key figure who shaped Japan's modernisation. His also helped the anti-Bafuku forces in toppling the Tokugawa Shogunate, and made many contributions to the industrialisation of Japan. Glover assisted the anti-Bafuku forces by supplying them with arms and warships (indirectly as this was illegal at the time). He also introduced the steam locomotives and cars to Japan, laid Japan's first telephone line, developed Japan's first coal mine in Takashima using Western technology (later acquired by Mitsubishi).

|

| Great view of Nagasaki port from the Glover House. |

The Glover House also overlooks Nagasaki Harbour and the Mitsubishi Shipyard. It seems rather apt, like a tangible reminder of his many contributions to Japan's shipping industry, as well as his service to Mitsubishi. Besides advising Mitsubishi, he built Japan's first Western style dry dock (also mentioned above), helped smuggle various Japanese abroad to study at foreign universities, such as the Choshu Five and trainees under Godai Tomoatsu. The Choshu Five became prominent members of the Meiji government, and one of them (Itou Hirobumi) became Japan's first Prime Minister.

|

| Greenhouse at the Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

My favourite part of the Glover House is greenhouse. It was filled with many beautiful and colourful plants, but I don't know if these are the original plants that grew there during Glover's time. The extensive bay windows have wonderful scenic views of the garden and the harbour area too.

|

| Kirin sculptures, Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

As for the Kirin sculptures in the greenhouse, they're clearly a reference to Kirin Brewery. As mentioned, Thomas Glover and Wilson Walker helped Iwasaki Yanosuke (Mitsubishi's 2nd president) establish the Japan Brewery, Kirin's predecessor.

|

| Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

As mentioned, Glover's wife, Tsuru, was Japanese. Like the rest of the house, her room is an interesting mix of East and West.

|

| Tsuru's room, Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

Apparently there are hidden rooms in the Glover House. The hidden rooms are in an attic above the servants' room, and is said to have been used to hide anti-Bafuku figures who visited. The Glover House was said to be a venue where Glover met with samurai from the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance.

|

| Hidden rooms in the Glover House |

Thomas Glover was succeeded by his son Kuraba Tomisaburou who also made significant contributions to Nagasaki's modernisation (mentioned above). Tomisaburo was Glover's son by his former Japanese lover Kaga Maki. Sadly, like with the Ringer family, Tomisaburo had a tragic end during WWII. Although Tomisaburou was a Japanese citizen, a part-Japanese born and raised in Japan, and despite the fact that he and his father had made many contributions to Japan, Tomisaburou was suspected as a spy by the Kenpeitai. From the onset of WWII, life became increasingly difficult for Tomisaburou and his wife Waka. In 1939, Tomisaburo and his wife were forced to leave Glover House, their home, because it overlooked the Mitsubishi shipyard and the Musashi battleship was being secretly constructed by Mitsubishi in Nagasaki at the time. As is well known, Mitsubishi manufactured Japanese military craft during WWII, including the infamous Zero fighter. Slightly off-topic here: the Kenpeitai's suspicions of espionage, especially in relation to Japanese military craft, was briefly but well illustrated in the anime film Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni (In This Corner of the World). Even Japanese people were suspected and interrogated by the Kenpeitai. Many with foreign connections or associations were treated with great suspicion by the Japanese military. Ironically, many distinguished military officers had such associations and even Western education, for instance Yamamoto himself.

|

| Stable at the Former Glover House, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

During WWII, Tomisaburou and his wife were under constant surveillance due to their mixed heritage, and also constantly harassed by the Kenpeitai. Unable to meet with their Japanese and foreign friends and business associates, they became isolated. His wife died in 1943, leaving him alone and depressed. Shortly after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and Emperor Showa's announcement of surrender, he committed suicide. It has been suggested that a possible reason for his suicide was that after dealing with suspicions of spying throughout WWII due to his mixed heritage, he feared living under constant suspicion and questioning by American occupation forces as a potential spy and war criminal. His grave is also located in Sakamoto International Cemetery, along with the graves of his father Thomas Glover and stepmother Tsuru (posted below).

Rekishi Shiryokan

|

| Rekishi Shiryokan, Glover Garden, Nagasaki |

At the exit of the Glover Garden is No. 16 Minamiyamate, now the Rekishi Shiryokan (literally "historical archive"). The plaque (in Japanese) explains that the building opened in 1860 as the lodging of the first American Consulate General. It then housed Kwassui Academy, the predecessor of present-day Kwassui Women's University (see also Former Alt House above). The building is said to be the oldest wooden Western-styled building in Japan. Originally built on land in Higashiyamate district owned by the Glover family, it was relocated to the Minamiyamate district, with its original appearance unchanged. Today, it is a historical museum containing the favourite items of the Glover and Siebold families, Christian materials, the Nanban trade's diamant glass (cut glass) and vidro glass, and items that tell of 19th century Nagasaki. At the time, blown glass was called biidoro, a borrowed term from the Portuguese "vidro", while cut glass was called giyaman, a borrowed term from the Dutch "diamant".

Nagasaki Traditional Performing Arts Centre

|

| Nagasaki Traditional Performing Arts Centre |

We wandered into the Nagasaki Traditional Performing Arts Centre (Nagasaki Dentō Geinō-kan) on our way out of the Glover Garden. The Chinese influences in Nagasaki's culture can be clearly seen in the museum's displays.

|

| Display of floats at the Nagasaki Traditional Performing Arts Centre |

On display are the dragon and boat-shaped floats that are used in the Nagasaki Kunchi, Nagasaki's famous festival that is held in October every year. The festival has been celebrated for around 400 years and features aspects of Chinese and Dutch cultures.

|

| Dragon dance, Nagasaki Traditional Performing Arts Centre |

The Chinese influence on Nagasaki Kunchi is the most obvious. One of the highlights of the Nagasaki Kunchi is the dragon dance, the Ja Odori, which was originally performed by Chinese residents in Nagasaki on Chinese New Year's Eve.

The Former Chinese Quarter

|

| Here lies the old Chinese quarter in Nagasaki. |

After visiting the Nagasaki foreign settlement area (above), we went to the former Chinese quarter, toujin yashiki in Japanese, which literally means "Tang people residence". I did puzzle about why Chinese people were referred to as toujin, as in "Tang people". During that time, China was referred to as tou, in reference to the Tang dynasty, a historical leftover from the Nara and Heian periods, when Japanese envoys returned from Tang dynasty China and introduced items, philosophies, beliefs and practices that had significant influence on Japanese culture.

As mentioned at the start of this post, Japanese relations with China date back to ancient times. Since at least 607 AD, diplomatic envoys travelled off Nagasaki's coast to China, and Japan traded with China and Korea long before the trade with the Portuguese. Nagasaki was where Japan's oldest existing Chinese settlement, where the Chinese community resided. Many Chinese migrants (mostly from the Fujian province) came to Japan in the 1600s, during the final years of the Ming dynasty. The Chinese were originally not restricted in their residences in Kyushu. However, during the sakoku period in 1635, the Shogunate confined the Chinese to trading at Nagasaki port and residing in a single area. The Shogunate's rationale for segregation was to restrict smuggling, the spread of Christianity (Nagasaki Part II), and to closely regulate the foreign community.

At first, the Chinese were restricted to residing in an area near Dejima where the Dutch were confined (more below). However, at some point in 1688, construction began in preparation for a Chinese quarter, the toujin yashiki. In 1689, the Chinese were moved to the Chinese quarter. The quarter measured around 28,000 square metres. Rent was around 10,000 or 16,000 taels per annum. The Chinese quarter housed on average of 2,000 people, at times even 5,000, giving rise to issues of overcrowding.

|

| The old Chinese quarter today, Nagasaki |

The policy also differentiated the Chinese between the non-residential Chinese, who were restricted to the Chinese quarter, and the more established residential Chinese. In the latter category were those who had been recognised as naturalised members of Japanese society (kind of equivalent to today's naturalised citizens); they were subject to the same restrictions as a Japanese commoner: free to move about Nagasaki, but prohibited from going abroad.

|

| The old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki. |

Those residing in the Chinese quarter were heavily restricted in their movements. Merchants were permitted to travel abroad and return, but generally residents of the Chinese quarter could not move around Nagasaki freely, they were not permitted to leave the Chinese quarter alone and had to be accompanied by shogunate officials.

These escorting officials were mostly comprised of descendants of the established residential Chinese, that is, the "naturalised" Chinese in the aforementioned category. They acted as go-betweens for the Chinese merchants and sailors with the Tokugawa Shogunate, and also mediated disputes within the Chinese quarter.

Restrictions of the Chinese quarter ended in 1859 when Nagasaki opened to international trade following the signing of the 1858 Harris Treaty. As Nagasaki became more open during the Meiji era, interest in the Chinese quarter gradually disappeared in 1868 as Chinese merchants were able to move freely again, and began to establish the present-day Nagasaki Chinatown (see below).

|

| Southwest corner of the old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

The former Chinese quarter route is not a popular tourist attraction, and we met no other tourists when exploring the old Chinese quarter. But it's a way to see what life for the average Nagasaki resident is like today, as the area today is mostly residential. The boundaries of the old Chinese quarter are indicated by 4 markers showing the northwest, northeast, southeast and southwest corners. All the 4 stone markers are located in nondescript spots like street corners, roadsides, and near people's residences. Some of the various structures in the former Chinese quarter, such as stone foundations, stairs and pathways, have survived and have been integrated into the present-day area. But otherwise, there is very little spots of interest.

|

| Southeast corner of the old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

Back then, the Chinese quarter was encircled by a moat, by a high earthen wall and dry gutter, as well as a bamboo fence. The entry/exit to the quarter had gates that could be locked from the outside. There was also a guardhouse at the entrance. The flow of people to and from the Chinese quarter was heavily regulated. The only Japanese permitted in the Chinese quarter were the shogunate officials and courtesans from the Maruyama pleasure district. Even the courtesans were not permitted to stay overnight, unlike in Dejima (below). Besides courtesans, women were not permitted in the Chinese quarter, and the residents were not permitted to bring their families to Japan.

|

| Remnants of the moat of the old Chinese Quarter |

A section of the moat that used to be the southern part of the Chinese quarter still exists today as a waterway. At the time, the moat served to separate the Chinese quarter from the outside. The flagstone paving at the current spot was laid during the Meiji era.

|

| Stone embankment from the old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

Besides the moat, the Chinese quarter was encircled by an earthen wall and dry gutter. When excavations to widen the streets in the area were undertaken, the remains of a 2m wide gutter and stone embankment, which corresponded approximately to the quarter's southern edge, were revealed. The stone embankment was dismantled and reassembled at the original site.

|

| Dry gutter of the former Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

Near the southeast corner is a preserved remnant of the former earthen wall and dry gutter that surrounded the former Chinese quarter. Back then, the quarter was separated from the surrounding neighbourhood by an earthen wall flanked by natural streams and by dry gutters carved from the rock face. The former dry gutters were revealed during street-widening excavations, which confirmed the southeastern border of the former Chinese quarter. The gutter was restored to its former state for preservation, and a portion of the former earthen wall has also been restored with reference to historic documents.

Also within the old Chinese quarter are 3 temples dedicated to Chinese deities: Kannondō (Guanyin Temple), Tenkodō (Heavenly Empress Temple), and Dojindō (Earth God Temple). Such temples are typical of Chinese settlements abroad.

|

| Kannondō, old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

The Kannondō (Guanyin Temple) was originally built in 1737, but it was destroyed in a fire in 1784 and rebuilt in 1787. The temple's original structure is said to have Okinawan influence. The current structure dates to 1917 and was constructed through the efforts of a Chinese merchant Zheng Yongchao. It was designated a municipal historic site in 1974.

|

| Kannondō, old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

Kannondō is, as evidenced by its name, dedicated to the Guanyin (Kannon to the Japanese), the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. Kannon is also a much revered deity in Japanese Buddhism.

|

| Tenkodō, old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

The next temple, Tenkodō (Heavenly Empress Temple) was established in 1736 by residents from China's Nanjing district. The original building was also damaged in a fire in 1784 and was restored in 1790. The current building dates from 1906. It was designated a municipal historic site in 1974.

|

| Tenkodō, old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

The presence of Tenkodō probably demonstrates Nagasaki's strategic importance with respect to the China-Japan trade. The temple honours Mazu, the goddess of the sea, also known as the Heavenly Empress (a title that was conferred in 1683). Worship of Mazu as guardian of the sea dates from the Song dynasty. Mazu originated from Fujian and was worshipped by many of the Chinese immigrants, merchants and traders (as mentioned, who were mostly from Fujian) before embarking on their journeys abroad. On arriving in foreign lands, the Chinese immigrants also generally carried a statue of Mazu to the shrine in a ritual procession. So it's typical to find a temple dedicated to Mazu wherever Fujian Chinese migrants have settled. Like in Yokohama Chinatown (see 2016 post). This procession is now recreated as the Mazu Procession during the Nagasaki Lantern Festival. We have something similar here in Singapore, in relation to our early Chinese community which also comprised largely of Hokkien immigrants, traders and merchants from Fujian province.)

Mazu is enshrined at the centre of this temple, with Guanyin (Kannon) to Mazu's right, and Guan Di to her left. This is why the temple was also sometimes called Kanteidō (Guan Di Temple), as it is also dedicated to the historical Chinese general Guan Yu (of Romance of the Three Kingdoms fame), deified during the Sui dynasty, and worshipped by many Chinese as a guardian deity, a god of war, and even a god of fortune.

|

| Dojindō, old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

The Dojindō (Earth God Temple) was originally built in 1691 by Chinese from Fujian province, with the shogunate's permission. It was built at the request of Chinese shipowners and other Chinese residents. It was destroyed in a fire in 1784, and was restored with donations form the 3 Chinese temples of good fortune in Nagasaki (Kofukuji, Fukusaiji and Sofukuji, which we didn't visit). Due to damage and aging, the temple was rebuilt and restored several times over the years, including in 1815, 1863, and over the Meiji period.

|

| Dojindō, old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

The temple was damaged from the WWII atomic bombing and fell into disrepair. In 1950, it was demolished, leaving only its stone foundations. The present building is a replica that was built in 1977. The temple was designated a municipal historic site in 1974.

|

| Dojindō, old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

The temple enshrines the Chinese earth god Tudishen (also Fudezheng Shen, god of blessing and virtue), widely revered by Chinese people since ancient times, as he is believed to protect the home, grant abundant harvest, prosperity and cure illness. The former Chinese residents in Nagasaki also practised the custom of stone monuments bearing inscriptions of the earth god beside gravestones.

|

| Fukken Kaikan (Hokkien Huay Kuan), old Chinese Quarter, Nagasaki |

Where there is a significant migrant Hokkien Chinese population, there will be a Hokkien Huay Kuan (Fukken Kaikan in Japanese), i.e. a Hokkien Clan Association. It was built around 1868, after the dismantling of the Chinese quarter. It was one of the grandest buildings in the Chinese quarter, and functioned as a public area where Chinese merchants met daily. Another shrine to Mazu was built within the premises. The building burnt down in 1888 and was rebuilt to its current structure in 1897. However, only the main gate and the Mazu shrine exist today as the main building was destroyed in the WWII atomic bombing. Unfortunately, it was closed when we visited, so we couldn't go inside. But apparently there is also a statue of Sun Yat-sen inside.

|

| Northwest corner of the old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

The northeast corner marker was the most difficult to find, as it was the most out of the way. It is located in a corner of a very narrow street in a quiet residential area at the top of a rather steep road. Hubby grumbled the whole way, especially at the end, where he said, "What? That's it?!" -\(;p)/-

|

| Northeast corner of the old Chinese quarter, Nagasaki |

Though only remnants of the old Chinese quarter remain, the Chinese left a lasting legacy in Nagasaki. For example, in Nagasaki's local food. Nagasaki's Chinese heritage is seen in Shippoku ryori, a Nagasaki specialty. The Chinese also left behind a Confucian temple (duh of course), as well as 4 community temples known as the Four Fortune Temples: Kofukuji (by people from Sanjiang), Fukusaiji (by people from Min'nan), Sofukuji (by the people from Fuqing) and Shofukuji (by people from Fujian). We ran out of time on this trip to visit these 4 temples, but we did visit the Confucius temple (see below).

Nagasaki Chinatown

|

| Nagasaki Chinatown |

Nagasaki Chinatown (Nagasaki Shinchi Chuukagai) was established around 1868 after Nagasaki was opened to international trade by the 1858 Harris Treaty. The Chinese left the Chinese quarter and began to have their residences at Shinchi Kurasho, an island that was constructed by land reclamation in 1702. At the time, the island housed storehouses which stored cargo that was transported by Chinese trading ships from China. Present-day Nagasaki Chinatown was an area called Shinchi where Chinese merchants gathered, and hung up billboards with their company names. At the time, there were many red-bricked buildings used by the Chinese, but were destroyed in a fire in 1947. Unlike Yokohama's Chinatown (2016 visit), the improvement and promotion of Nagasaki Chinatown as an attraction only really began in 1984. The 4 gates representing the Four Symbols (the Shishin in Japan) were built around 1986 as well. Around 1987, Nagasaki Chinatown became the centre of the Nagasaki Lantern Festival.

The local cuisine of Nagasaki has a lot of Chinese influence as well. Some of the must-try Nagasaki foods, especially around Chinatown, are the kakuni manju (pork belly buns), goma dango (fried sesame ball, after the Chinese jiandui), chanpon, and sara-udon (like HK style crispy chow mein).(/p>

|

| Chanpon, a local Nagasaki dish |

Our first taste was at some eatery near Glover Garden (above). Hubby had the chanpon, a Nagasaki dish that includes thick springy noodles, pork, seafood, vegetables, and a broth of pork and chicken. The dish is supposedly based on a Fujian dish called ton'ni'ishiimen, and is said to have been created by the founder of Shikairou, Nagasaki's longest-standing established Chinese restaurant (since 1899). Back in the day, the dish was just called "Chinese Noodles".

|

| Nagasaki kakuni, another Nagasaki regional food |

For lunch, I had tried a rice bowl with Nagasaki kakuni, Nagasaki-style braised pork belly dish. Buta kakuni (braised pork belly) became available in Nagasaki through the Chinese during the sakoku period. Originally from Chinese cuisine (probably from Dongpo pork), the dish has evolved to the Japanese palate, and is now a meibutsu of Nagasaki. The pork belly is simmered in a braising liquid of dashi, shoyu, mirin, sugar and sake; not unlike the Chinese method but with Japanese ingredients, and the flavours are distinctively different.

|

| Dinner at Kyōkaen, Nagasaki Chinatown |

For dinner we had Chinese, Nagasaki-style, at Kyōkaen, a Chinese restaurant in Nagasaki Shinchi Chinatown. It was located near the entrance. Occupying 5 floors of a building, it is apparently one of the largest Chinese restaurants there. We didn't order much: half a Peking duck, gyoza (Chinese guotie), kakuni manjuu (Chinese kong bak bao), stir-fried beef with peppers, and sweet corn egg drop soup (Chinese jīdàn yùmǐ tāng).

|

| Kakuni manjuu, Kyōkaen, Nagasaki Chinatown |

One of the recommended dishes at Kyōkaen is the kakuni manjuu. They were pretty good. It was subtly sweet, perhaps a little more to the Japanese palate there. Personally, I'd like the gravy to be stickier, and I wouldn't have minded a little more spices in it, like five-spice. This is fairly similar to how we do pork belly buns (kong bak bao) at home too, just that the Chinese recipe calls for soy sauce, rice wine and spices in the braising liquid. The super soft braised pork belly enveloped by the steaming fluffy bun.... This always conjures up the image of a soft bed with a warm, fluffy quilt. Comfort food!

Overall, the food was decent. As people who are used to the higher standard of Chinese food available at home, Hubby and I were probably being picky. In any case, most of the time, we don't eat Chinese cuisine in Japan. After all, why when everything else is so delicious?

Confucius Shrine

|

| Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

Of course when it comes to Chinese culture and history, how can we forget Confucius, singly the most famous Chinese philosopher in history whose teachings is one of the most prominent and lasting among the Hundred Schools of Thought. The Chinese in Nagasaki certainly did not forget enshrining him here, in the Confucius Shrine (Kōshi-byō).

A Confucian temple (mausoleum), it was first built in 1893 by Nagasaki's Chinese residents with the support of the Qing dynasty government, and used materials sourced from China. It housed a Confucian sanctuary and primary school. The temple's buildings were damaged by the atomic bomb in WWII, and restored in late 1967. It was then extensively renovated in 1982. This Confucian temple and Tokyo's Yushima Seidō are the most famous of the Confucian temples in Japan. This one in Nagasaki however is considered to be the only full-scale Chinese style Confucius temple in Japan.

|

| Reiseimon and Hekisui Bridge, Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

At the front is a small garden with a pond. Over the pond arches a small Chinese style stone bridge called the Hekisui Bridge. The name hekisuibashi literally means "jade-green water bridge". The simple stone gate in front of the Hekisui Bridge is the Reiseimon. Apparently the style of this gate is the model for Shinto shrine torii gates in Japan.

|

| Hekisui Bridge and the Reiseimon, Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

To the left of the Reiseimon is a male Chinese pistache tree, to the right is a female one. Both these trees were planted in 1893 when this temple was built. The Chinese pistache (huángliánmù in Chinese, kainoki in Japanese) is known as Confucius' Tree, and is always planted in places related to Confucius. Also, on one end of the pond is a miniature hillock of grey stones, which frankly I still fail to fully appreciate. The stones used are Taihu stones, a rare porous limestone found at Lake Tai in Jiangsu, China. The stones in this miniature hill were a donation from Jiangsu Province.

|

| Gimon, Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

Facing the Reiseimon and the Hekisui Bridge is the Gimon. The Gimon is the formal inner main gate (second gate) of the temple. This gate dates back to 1967, when it was rebuilt after the original was destroyed by a typhoon in the early Showa period. The Gimon is brightly coloured and ornately decorated with classic Chinese icons and carvings. Vermilion was considered the colour of joy and thought to ward off evil. The yellow-glazed ceramic roof tiles are actually a status symbol. During the Qing dynasty, by law only certain colours were permitted to be used by certain classes. Thus the colour of the roof tiles of Chinese palaces and mausoleums denoted the status of their masters. Yellow tiles could only be used for the Chinese emperor's palaces and mausoleums. At the time, Confucius was revered and given equal treatment as the Chinese emperor and was therefore permitted to use yellow-glazed tiles.

In front of the Gimon stand a pair of Chinese stone lions. These stone lions were produced in Hui'an County and given to the temple by the Fujian Province in commemoration of the temple's 90th anniversary. Also flanking the Gimon are a pair of Bixi stone commemorative stela. The stone stele on the left is inscribed with a poem by Tang dynasty artist Wu Daozi in praise of Confucius. The stele on the right is inscribed with a poem likewise praising Confucius, by Song dynasty artist Mi Fu. The stone stela are generally known as Bixi because of the tortoise-like dragon sculpture, which depicts Bixi, one of the mythological sons of the Dragon King.

The Gimon is actually made up of 3 entrances side-by-side, with the doors of the centre entrance closed. Traditionally, the gates to Chinese mausoleums were built in odd numbers, and the centre gate was a sacred gate that only the Emperor could pass through, and therefore remained closed.

|

| The west corridor (seibu) of the Confucis Shrine containing stone tablets of the Analects of Confucius, Nagasaki. |

The Gimon leads to a wide courtyard flanked by life-sized stone statues of Confucius' 72 disciples, and a pair of corridors to the east and west (collectively called Ryobu). The east and west corridors display marble stones carved with the entire text of the Analects of Confucius.

|

| The courtyard with the 72 Sages and the Taisei Hall, Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

Across the courtyard is the Taisei Hall, also in classical Chinese architecture, which dates back to the time of the shrine's construction in 1893. The Taisei Hall contains, among other things, a seated statue of Confucius and mortuary tablets of his parents, the Twelve Philosophers, etc. The statue of Confucius has been consecrated at Qufu and, at 2m high, is the largest seated statue of Confucius in Japan.

|

| Chinese History and Palace Museum, Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki |

We popped into the museum at the back of the shrine complex, the Chinese History and Palace Museum. It was built in 1983 to celebrate the shrine's 90th anniversary since its founding, and was intended to promote Sino-Japanese relations. Unfortunately photography in the museum wasn't allowed. There were many Chinese artifacts displayed, including intricate works of carved wood and ivory, Chinese pottery, as well as many treasures from the Beijing Palace Museum. Also photographs of the old Silk Road, models of early Chinese inventions, and documents relating to the shrine itself.

Sakamoto International Cemetery

|

| Sakamoto International Cemetery, Nagasaki |

Bearing testament to Nagasaki's history as an international trading port, Nagasaki has 3 international cemeteries: Inasa International Cemetery (which is the oldest), the Oura International Cemetery, and the Sakamoto International Cemetery. We only had time to visit one, so we went to the Sakamoto cemetery, which happens to be the better known of the 3. I say "we" but I actually mean "me"; Hubby found my intention to visit rather ghoulish.

The Sakamoto International Cemetery (Sakamoto Kokusai Bochi) was established in 1888 as a substitute for the Oura cemetery. The latter was established in the 1860s and located near the Nagasaki foreign settlement. Sakamoto cemetery has around 400 graves of people of many nationalities.

|

| Grave of Nagai Takashi, Sakamoto International Cemetery |

Sakamoto cemetery is probably the better known because it contains the graves of Thomas Glover and his family, as well as atomic bomb survivor Dr. Nagai Takashi (see Nagasaki Part II).

|

| Graves of Kuraba Tomisaburo (left) and Thomas Glover (right), Sakamoto International Cemetery |

So we found the Glover family graves, where Thomas Glover, his wife Tsuru and his son Kuraba Tomisaburo are buried (mentioned above). Looking at their somewhat simple grave markers, it's a little hard to believe the legacy left behind by them.

|

| Hebrew burial plot at Sakamoto International Cemetery, Nagasaki. |

Within the Sakamoto cemetery is a Hebrew cemetery plot marked by an arched stone entrance inscribed with the Hebrew words "Bet Olam" (meaning "eternal home"). I was surprised to learn that around the 1880s, Nagasaki had a small but thriving Jewish community. Apparently, the Jewish people have travelled to Japan as early as the 16th century but they did not settle in Japan until 1853, after the arrival of Commodore Perry.

|

| Grave of Sigmund D. Lessner, Sakamoto International Cemetery |

Around the 1861, the first Jewish settler arrived in Japan, in Yokohama. In the 1880s, Jews fleeing the Russian Empire's pogroms settled in Nagasaki. The community began various shops and businesses in the Nagasaki foreign settlement (posted above).

The Hebrew plot contains about 30 graves. Occupying the most prominent spot is the grave of Sigmund D. Lessner who was an eminent merchant and leader within Nagasaki's Jewish community. In 1896, Lessner, along with another Jewish merchant Haskel Goldenberg, established the Beth Israel Synagogue (which no longer exists).

During WWI, Lessner had to suspend his business as he was an Austrian national and trade with enemy subjects was prohibited by the British and Japanese. During that time, some of his properties were also confiscated by the Japanese government. After WWI, in 1919, Lessner revived his business, but he unexpectedly died of heart failure in 1920. Following the decline of Nagasaki as a foreign trading port, and subsequently the outbreak of WWII, the Jewish residents in Nagasaki left. This plot is the only physical reminder of the Jewish presence in Nagasaki today. (That said, there are a small number of Jewish descendants in present-day Japan, mainly in Tokyo and Kobe.)

|

| Boxer Rebellion French soldiers cemetery plot |

Within the Sakamoto cemetery is also a plot containing the graves of French soldiers killed during the Boxer Rebellion in China. A little further down, also encircled by a short brick wall, is the plot containing the graves of Vietnamese who were killed during the same rebellion.

Dejima

|

| Dejima, view from the West Gate. |

Now we get to Dejima (literally "exit island"), today a reconstruction of its 19th century appearance with 10 representative buildings. The fan-shaped reclaimed island of Dejima was constructed between 1634-1636 under the orders of the Tokugawa shogunate. On its completion, the Portuguese were moved to Dejima, as part of the shogunate's attempt to control foreign trade and the spread of Christianity. As mentioned at the start, the Portuguese were then expelled in 1639 as a response to the Shimabara Rebellion, leaving the Dutch (who had assisted the shogunate during the said rebellion) as the only Western country with trade access to Japan. The Dutch had a trade monopoly with Japan, and traded from their trading base in Hirado until around 1640.

|

| Miniature Dejima, a 1/15th scale model of Dejima based on Kawahara Keiga's illustration "Nagasaki Dejima" showing the island around 1820. |

In 1641, the shogunate made the Dutch move to Dejima, ostensibly because the Dutch failed to comply with certain strict sakoku rules. It has also been suggested that the shogunate wanted to remove control of the Dutch trade from the Matsura clan which ruled Hirado. As a result, Dejima became the only trading port between Japan and Europe during Japan's sakoku period, as well as the centre of Dutch study, making Nagasaki the centre of Rangaku in Japan.

|

| Remains of the southern embankment wall at Dejima, Nagasaki |

Similar to the Chinese at the Chinese quarter, the Dutch were strictly confined to Dejima. Dejima was connected to the mainland by a single bridge, the Dejima Bridge (more below). Like the Chinese quarter, Dejima was guarded and had locked gates. Access was severely limited. The Dutch were not permitted to bring their families to Japan. The Dutch residents also required permission to leave Dejima. The Japanese in general were not permitted to enter Dejima. Entry was only permitted to Japanese merchants, shogunate officials, go-betweens (e.g. interpreters) and Japanese staff that worked on the island (e.g. scribes, secretaries, cooks, guards, etc). Women in general were also not permitted except for the designated courtesans. Unlike at the Chinese quarter (above), courtesans were permitted to stay overnight or for longer periods at Dejima.The Dutch also had to make regular visits to Edo to pay homage to the shogunate, similar to the practice done by daimyo (sankin-kōtai).

As we headed towards the entrance to Dejima, we passed a restored section of Dejima's southern embankment wall, which was discovered during excavations in 2003-2004. Dejima used to be surrounded by this stone embankment wall. The excavations revealed that the southern section, faced the harbour and was vulnerable to typhoon damage, had undergone several repairs. They also revealed that the landing platform on the west side of Dejima had also been extended over time. Also revealed were the remains of a pebbled pavement on the street running through Dejima, as well as other structures and artifacts.

|

| Stone posts of the former Dejima Bridge, No. 14 Warehouse, Dejima |

Displayed in the No. 14 Warehouse are the stones that are are thought to have been the main posts of the Edo period stone Dejima Bridge (Dejima-bashi). They were discovered during a construction project and were donated to the Nagasaki City Hall. One of them has an inscription that shows the kanji characters 出島橋 (Dejima-bashi). Square holes have been cut through the stones to hold lanterns. The original bridge leading to Dejima was a wooden bridge that was replaced with this stone bridge in 1678. For decades, the stone bridge served as the only link between mainland Nagasaki and Dejima. It was demolished as part of the diversion of the Nakashima River in 1885.

|

| 1/30th scale model of the former Dejima Bridge, No. 14 Warehouse Dejima |

Also exhibited was a 1/30th scale model of the former Dejima Bridge, showing the entrance to Dejima and the Edo-machi neighbourhood. This model was recreated based on excavation findings in Edo-machi and the style of existing bridges in Nagasaki at the time. The front gate was recreated based on old maps and illustrations of Dejima, the Dejima scroll painted by Ishizaki Yushi, and other historical documents.

|

| Remains from the 1798 Great Fire at Dejima, No. 14 Warehouse, Dejima |

In 1798 a severe fire broke out in Dejima and destroyed the western half of the island. The remains found were of a pond remaining from before the fire. The pond was man-made, using amakawa, an orange-coloured clay and limestone mixture. It was later filled in, and part of the foundation of No. 14 Warehouse was later built on top.

|

| Chief Factor's Residence, Dejima, Nagasaki |

The largest building on Dejima is the Chief Factor's Residence. Used as his residence and also to entertain Dutch merchants and various officials, the building was built to reflect his important status. The Chief Factor, more accurately the opperhoofd, was the chief executive officer of the Dutch trading post. The Japanese continued to refer to this position as kapitan (from the Portguese "capitão"), which they had done during trade with the Portuguese.

Other than the building's distinctive turquoise and white facade, another prominent feature of the Chief Factor's Residence is the triangular-shaped staircase that leads to the 2nd floor from the exterior. The architecture is also an interesting mix of Japanese and Western architectural styles. The interior truly showcases the distinctive living spaces and lifestyles of the Dutch residents at the time. The buildings on Dejima were fundamentally Japanese in style, but they also exuded an European atmosphere because of various changes made by the Dutch residents. At the time, Japanese people used illustrated bamboo paper in sliding doors, but the Dutch used it to cover the walls and ceilings of their homes, very much like wallpaper. The Dutch residents also used paint on building materials and installed glass windows in the grooves for the sliding screens, both of which fascinated the Japanese. Inside, the rooms are furnished with tatami mats, but the Dutch placed European-style furniture on top of the mats and used European style furnishings.

|

| Room in the Large Vestibule at the Chief Factor's Residence, Dejima, Nagasaki |